Interview with Maryam Ego-Aguirre: Seeing the Sacred in All Sentient Life

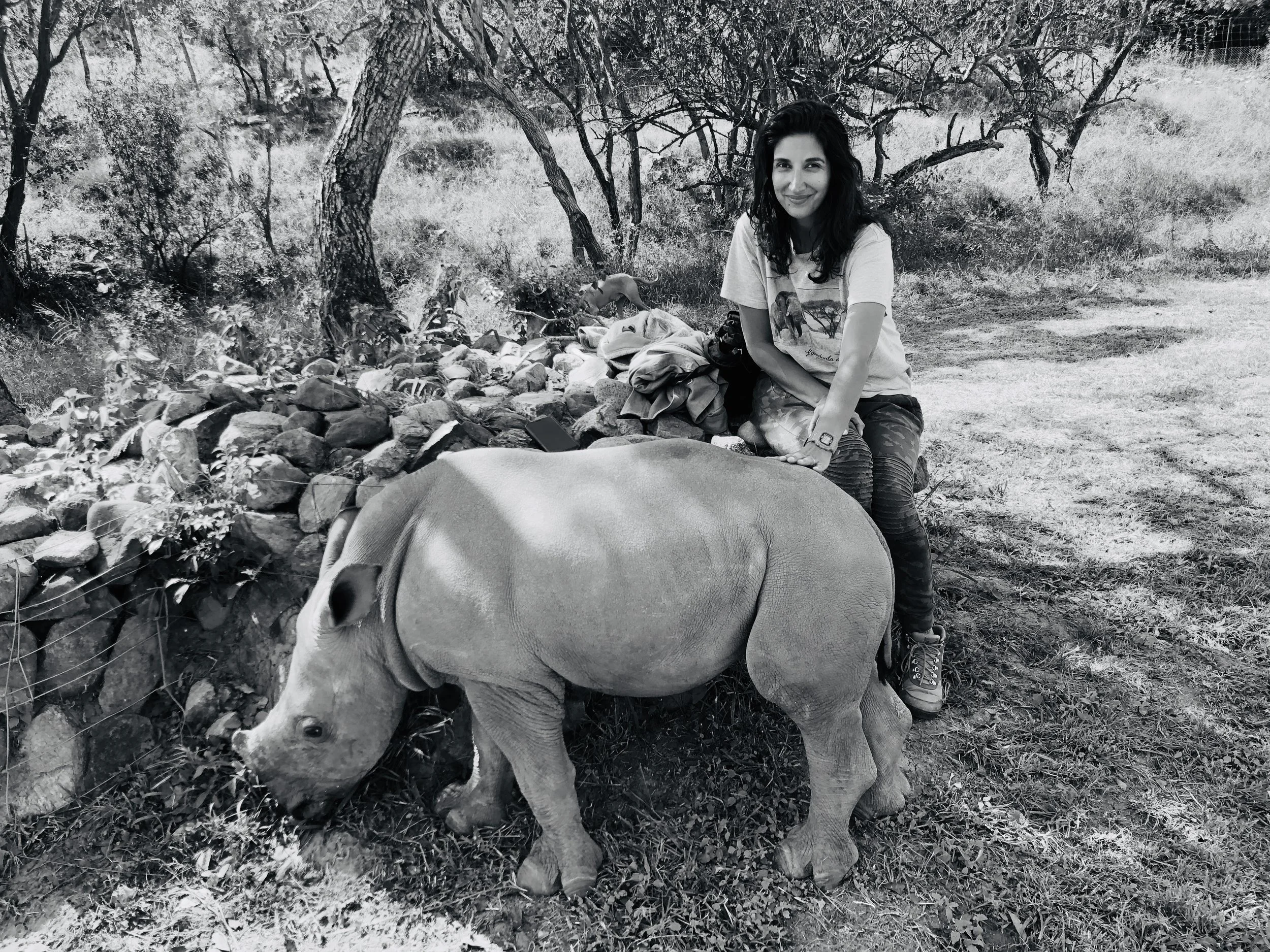

Maryam Ego-Aguirre is a surrealist photographer and longtime animal rights advocate whose work doesn’t just speak—it confronts. Her art and writing challenge the way we see animals, nature, and ourselves, asking us to look beyond comfort and into conscience. What she creates is more than visual—it’s emotional, philosophical, and deeply ethical.

In this interview for the Middle East Vegan Society, Maryam shares her personal journey, her reflections on compassion, and how her cultural background and creative practice have shaped her activism. Her words are poetic, honest, and rooted in a fierce commitment to truth. It was a privilege to step into her worldview.

Can you share a bit about your journey—what shaped your worldview and led you to embrace animal rights and veganism?

I grew up surrounded by contradictions—love and violence, tenderness and cruelty existing side by side. From a young age, I felt the weight of what others called ‘normal.’ I watched animals treated as food, spectacle, or commodity, and something inside me recoiled. I could not reconcile their suffering with the claims of morality adults insisted on. At twelve, I stopped eating meat, though the word ‘vegan’ wasn’t yet in my vocabulary. Over time, my own awakening deepened: it wasn’t only about what we eat, but about how we relate to life itself. The moment I saw animals as subjects of their own lives—not objects for our use—I understood I had a responsibility to act differently. My art, my advocacy, my choices all flow from that recognition.

How has your cultural background informed your sense of justice and empathy?

My father was Iraqi, from Babylon, and my mother was Persian. Both came from civilizations that once held wisdom in high regard—yet I also witnessed how those same worlds, over time, were corrupted by dogma, patriarchy, greed and violence. Their stories of exile and survival impressed upon me that injustice is not theoretical; it is lived in bodies, in families, in histories. Growing up in America as their child, I stood at the crossroads of East and West, never fully belonging to either. That liminal space taught me to see hypocrisy quickly, to distrust power when it cloaks itself in virtue, and to hold empathy as my compass. If my parents taught me anything, it is that survival without compassion is empty, but compassion rooted in justice can endure beyond lifetimes.

You’ve spoken about mercy as a universal force. How do you define compassion in a world that often limits it by species or utility?

Compassion is not a sentiment—it is a discipline. It is the refusal to draw arbitrary lines between who is worthy of care and who is not.

Humans are quick to extend mercy when it serves them and withhold it when it requires sacrifice. But mercy that is conditional, is not mercy at all; it is transaction.

True compassion means seeing the calf torn from her mother, the elephant chained in the name of ‘tradition,’ the pig who simply wants to live—and recognizing in them the same sacred will to exist that beats in us. It means understanding that to diminish them is to diminish ourselves.

What do you believe is the most urgent ethical challenge facing our species today?

The greatest challenge is our addiction to domination—over animals, over the earth, over each other. We disguise it as progress, as culture, as profit, but beneath it lies the same sickness: the belief that might makes right. Climate collapse, factory farming, endless wars, systemic exploitation—all are symptoms of this disease. Unless we confront the root, our cleverness will destroy us. The urgency is not merely to innovate or reform, but to transform the very story we tell ourselves about power, responsibility, and what it means to live in harmony with the world, rather than at war with it.

What role do you think artists can play in shifting public consciousness around ethical issues?

Artists are translators of the unseen. We can take what others ignore—the cry of an animal, the silence of a forest felled, the hidden cost of a luxury—and render it visible, undeniable. Art bypasses the intellect and reaches the heart, the place where change truly begins. But the artist’s role is not to comfort; it is to disturb the comfortable illusions people cling to. We hold up the mirror and say: this is what you are, this is what you choose, this is what it costs. In that reflection, people either turn away—or begin to awaken.

How do you stay grounded or hopeful in the face of widespread cruelty and indifference?

Hope, to me, is not naïve optimism. It is endurance. I stay grounded in the living world—in the quiet presence of my dogs, in the resilience of a tree breaking through concrete, in the companionship of wild creatures who remind me that purity still exists outside of human greed. I remind myself that history is not only written by empires; it is also written in the invisible acts of care, resistance, and truth-telling. Even when cruelty feels overwhelming, I know that to give in to despair is to abandon the innocent. And that I cannot do.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave—through your art, your advocacy, or your presence?

I don’t seek monuments or applause. My hope is simpler, but also harder: that my life, in whatever small measure, eases the suffering of those who cannot speak for themselves. That my art opens a few eyes, that my words plant seeds of conscience, that my choices reflect integrity, even when it costs me. If, after I’m gone, someone chooses mercy over convenience, or sees an animal not as a thing, but as a being because of something I created or said—then that is enough. My legacy, I hope, is not about me at all, but about aligning with the eternal truth that life is sacred, and cruelty is never justified.

Conclusion: Mercy as Mirror

Maryam Ego-Aguirre does not ask for comfort. She asks for clarity. Her life and work challenge us to look beyond the borders of species, culture, and convenience—and to see the sacred in all sentient life. In her words, mercy is not optional. It is the pulse of existence.

And in that pulse, we find not only the truth of others—but the measure of ourselves.